Lana Del Rey’s call for a more intersectional feminism was misplaced and off-colour

By Niamh Quinn / 27 May 2020

Illustration by Philippa Mwayi

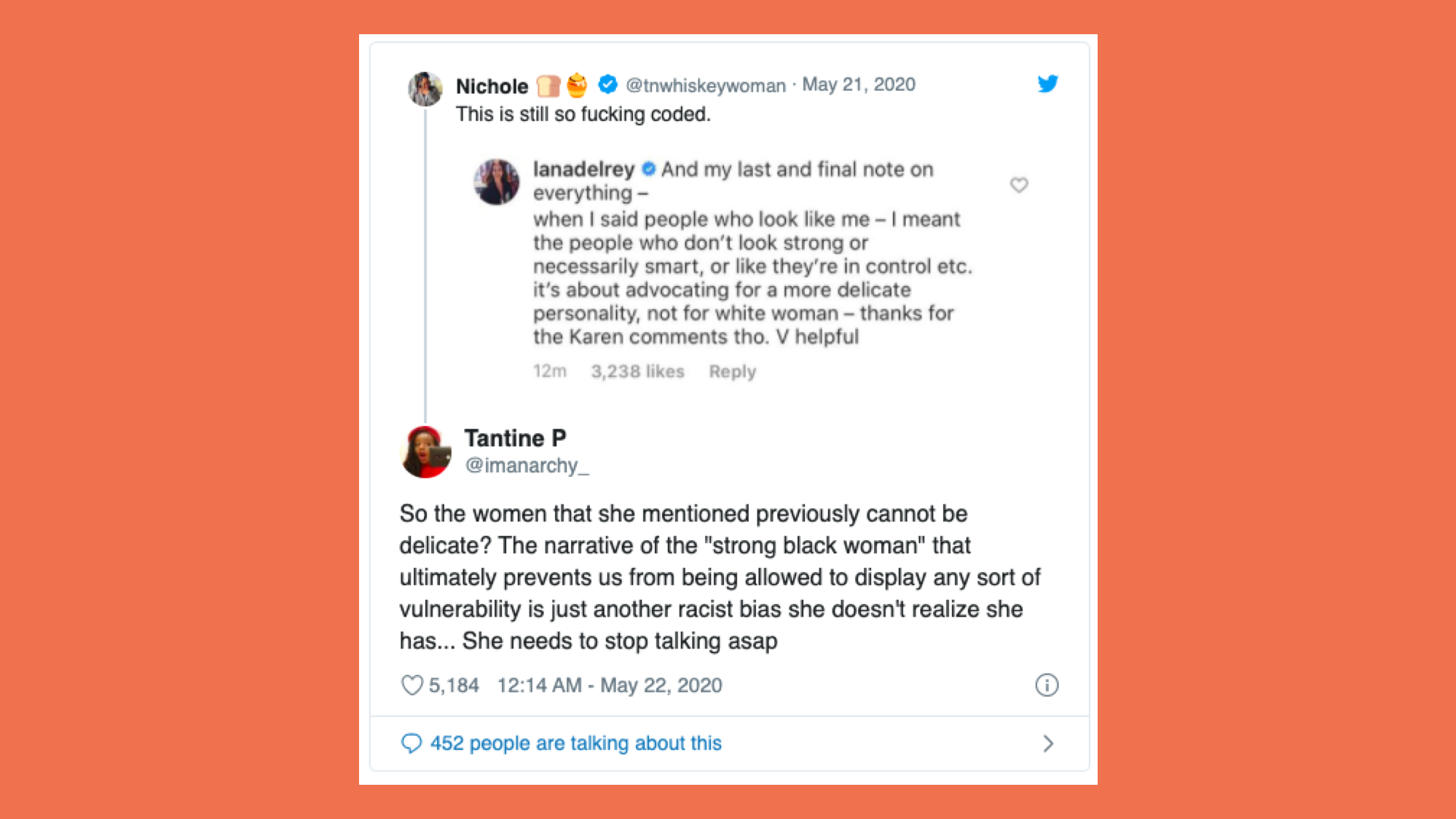

On 21st May 2020, Lana Del Rey clicked publish on a post that sent the internet into a frenzy, reopening up a conversation about why white women just cannot seem to critique societal injustice without dragging WOC.

Catapulting online conversation from Covid-19 to Karen, the last couple of weeks have seen Alison Roman and Lana Del Rey simultaneously shoot themselves in the foot and shoot to the top of the Twitter Trending Leader board... In an Instagram post berating the disproportionate criticism of the “fragile woman”, Del Rey participated in a blinkered Oppression Olympics, acknowledging the existence of a vertical hierarchy but misplacing herself within its structure.

“Doja Cat, Ariana, Camila, Cardi B, Kehlani, Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé have had number ones with songs about being sexy, wearing no clothes, fucking, cheating etc.” she commented, “Can I please go back to singing about being embodied, feeling beautiful by being in love even if the relationship is not perfect, or dancing for money, or whatever I want – without being crucified or saying that I’m glamorising abuse?”

As a white woman, Del Rey’s contribution to the intersectional feminism conversation should have been articulated thoughtfully and compassionately. Name dropping black women in order to create a framework in which you epitomise white fragility and victimhood isn’t a good look. What’s more, while Del Rey made these comments, seemingly from a place of blissful ignorance, asserting:“This is the problem with society today, not everything is about whatever you want it to be. It’s exactly the point of my post — there are certain women that culture doesn’t want to have a voice it may not have to do with race I don’t know what it has to do with. I don’t care anymore but don’t ever ever ever ever ... call me racist”, she fails to recognise the deep-rooted racial implications that exist in the fragile/strong dichotomy she introduced in her post. Albeit unintentionally, when Del Rey labelled herself “the kind of woman who says no but men hear yes - the kind of women who, are slated mercilessly for being their authentic, delicate selves” she contributed to the narrative that has been oppressing WOC since the beginning of time and made intersectional feminism necessary.

In an age-old narrative, perpetuated still by popular culture and the media, black women have been placed into two dominant paradigms: the angry, aggressive “Sapphire” caricature and the hypersexualized “Jezebel” caricature. Adia Harvey Wingfield, professor of sociology at Washington University in St. Louis expands this idea, noting that “white women have historically been the default when it comes to mainstream, cultural ideas of what femininity is and what it looks like”. From Serena Williams to Michelle Obama and Meghan Markle, successful black women are constantly pilloried in the press, cast into the angry black woman trope, proving that if your identity exists at the intersection between race and gender, you are stripped of the luxury of the fragile stereotype that protects white women. Speaking of the media’s reaction towards Serena Williams in the US Open, Law Professor Trina Jones said "Black women are not supposed to push back and when they do, they're deemed to be domineering. Aggressive. Threatening. Loud."

Below is Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech delivered to the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio, demonstrating that the roots of this narrative are in slavery and dehumanising black women:

What is clear is that Del Rey’s decision to use black women to create a framework for her own victimhood was wrong. Channelling her frustration with the patriarchy towards other women, even indirectly, was inarguably misplaced and off-colour. The white heteropatriarchal society in which we live and within which white feminism is firmly planted has created a fertile ground for Lana Del Ray to sit delicately and 50s fashion-clad, in blissful ignorance of the hurdles black women have had to overcome just to have a seat at the table with her and other white female stars.

However, in demanding a safe space for women to express experiences of abuse and complicated relationships with intimacy and violence through their art, Lana Del Rey was not unreasonable. In fact, feminism has failed the Ultraviolence singer many times, turning a blind eye to attacks launched on her identity and artistry in a way that has sought to undermine her selfhood with misogyny and dehumanising language. “I’m fed up with female writers and alt singers saying that I glamorise abuse,” wrote Del Rey, “when in reality I’m just a glamorous person singing about the realities of what we are all now seeing are very prevalent emotionally abusive relationships all over the world.”

Feminism shifted from a second wave which accepted the empowering notion of a commonality of trauma and abuse in the experiences of many women to a third wave ‘power feminism’, that Benjamin A. Brabon and Stéphanie Genz touched upon in their 2009 text Post Feminism “identifying with other women through shared pleasures and strengths, rather than shared vulnerability and pain.” In fact, in Naomi Wolf’s book Fire with Fire (1993), she rewrites the feminist narrative, stripping from women the right to believe in their own victimisation, considering it an obstacle that needs to be overcome. “This feminism has slowed women’s progress, impeded their self-knowledge, and been responsible for most of the inconsistent, negative, even chauvinistic spots of regressive thinking that are alienating many women and men” (147).

However, as Lana said “News flash! That’s just how it is for many women.” Denying women the right to artistically express a common experience in the name of female essentialism isn’t progressive or unifying, it’s ostracising. In this way, Del Rey’s 50s aesthetic is astute and effective, materialising a struggle with selfhood and identity in a modern context, reflected in her lyrics such as:

“I was always an unusual girl

My mother told me that I had a chameleon soul

No moral compass pointing due north

No fixed personality”.

Basically, what I have taken from all of this controversy is that Lana Del Rey has been failed by feminism, but she has used WOC to leverage herself as the prime candidate for exclusion and criticism. In doing this and in implementing a strong/fragile dichotomy in which she is the victim, Del Rey exposed her ingrained racial bias. We’re not here for cancel culture, Lana, but educate yourself and do better.

Art by

Words by

Share this article