‘We will *remove* them at the beaches’

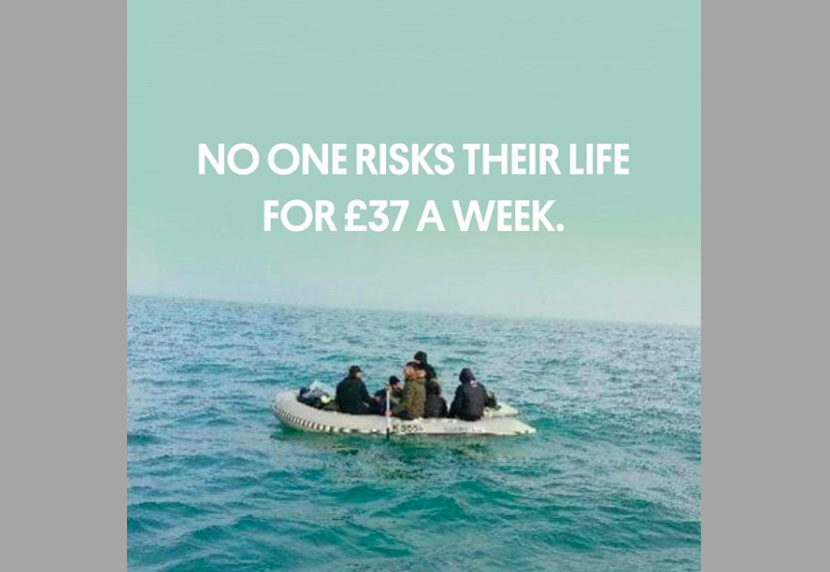

Britain’s militaristic response to the surge in Channel crossings fuels violent narratives of racism and hate.

By Florence / 12 August 2020

An invasion is what happens when military force is used to enter another country, violently.

For many in the UK, the term occurs at a historical or geographic elsewhere, permeating our western realities only via the breakfast news. Invasion is not a small group of Afghan, Iranian and Iraqi refugees silently arriving on a deserted Kent beach in the early hours of Thursday morning, as stated by Nigel Farage last week.

Since the beginning of 2020 over 4,100 migrants have travelled to the UK on small, often inflatable, boats. This is a sharp rise from 2019, where Channel crossings were predominantly undertaken via plane or lorry, methods that Covid-19 has made unavailable. The recent good weather has made sailing the safest and most viable option for those seeking refuge in the UK. This figure has been used to thrust anti-migrant discourse into headlines often with little context with which to understand it. The 36,000 applications for asylum made in the UK in 2019 were dwarfed by the 165,615 in Germany, 151,070 in France and 117,800 in Spain, numbers that reveal recent actions by British ministers as unduly militaristic.

Home Secretary Priti Patel has used the crossings to demonstrate her hard-line approach, deploying an RAF A400M Atlas plane to encircle the English side of the Channel at a height visible from sea level. While the RAF has defended this as an investigative flight that supported the British Coast Guard in locating migrant boats, it must also be seen as a premonition of the hostile environment that would be greeting the refugees upon their arrival. No doubt recalled the warzones from which many of them had fled. Patel has appointed a “clandestine Channel threat commander”, furthering the alignment of asylum and warfare. This rhetoric only serves to fuel the suspicion and hatred of people in need that is insidious in Britain’s far-right.

Image via @chooselove

Boris Johnson echoed Patel on Monday when he described the crossings as “dangerous and criminal”, along with stating the refugees and asylum seekers have “blatantly come here illegally.”

Johnson’s statement quickly incited a surge of criticism from humanitarian groups who reminded him that it was not illegal to seek asylum under Article 31 of the UN refugee convention. Johnson’s focus on the muddied criminality of these transportations- giving disproportionate attention to the illegal human trafficking that is sadly inherent in many asylum passages- alerts us to some of the other law-breaking voyages with which he has been recently associated.

In early July, Stanley Johnson, Boris Johnson’s father, travelled to his second home in Greece despite the government guidelines that British nationals should avoid all but essential travel. Boris Johnson refused to criticise the trip, instead proposing the media approach his father directly. Along a similar vein, Dominic Cummings travelled to Durham in May despite showing Covid-19 symptoms, to supposedly ensure childcare, should he and his wife deteriorate. Boris Johnson did not condemn this trip, stating that Cummings was acting out of parental instinct. One is left wondering if such sympathy is held in Parliament for the displaced parents risking their own lives in the hope of safer futures for their children in the UK. Donald Trump’s separation of families at the Mexican border in 2018, where children were placed in holding cages, set a new low for western leaders’ ill-treatment of migrant families. The UK is currently demonstrating a similar lack of humanitarianism.

Image via @chooselove

Moral panic is entrenched in the UK’s discourse on migration as it inflames multiple nationalistic neuroses simultaneously:

The realisation that borders are permeable and uncontrollable (as hypothetic constructions tend to be), the threat of the poor and racialised Other benefitting from Britain’s welfare system, and the racist delusion that migrants pose a threat to archaic ideals of white purism (even though the UK currently houses less than 1% of the worlds refugee population). Hostile tropes of nationalism have been exacerbated by the pandemic, which has torn through low-income, often migrant, communities resulting in Britain’s death rate to be disproportionately populated by non-white groups. By using wartime rhetoric to discuss migration Patel, Farage and others of Boris’ coterie are directly fuelling narratives of racism that locate violence, rather than rehabilitation, at the core of Britain’s political strategy.

Rather than circulating the dehumanising coverage of wet, tired, and scared individuals clambering from rubber dinghies, British media needs to face the history of abuse and subjugation that lurks behind the shocking images. Our lives are historically enmeshed with those we dare to call Other. 120 people who were intercepted on the Channel on the 4th August came from Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Palestine, Sudan and Yemen. Of these countries, two were invaded in not too distant history by a coalition that included the UK; one has been starved into famine by a military government supplied by British weaponry; one is in ongoing conflict with UK ally Israel; and the others, many of which are former British colonies, are suffering well-documented persecutions of ethnic groups sowed from the fertile soil of racism left by Empire. Acknowledging these connections makes the government’s actions even more reprehensible and underlines the need to challenge divisive narratives that illegitimise certain groups right to safety.

A list of ways you can express solidarity with those suffering from displacement:

https://helprefugees.org/get-involved/

https://www.refugee-action.org.uk

https://www.gov.uk/help-refugees

Words by

Share this article