dirty talk: let's talk about it

By Aya Kurteva / 22 April 2021

Illustration by Jade Pughe / of Samira Raheem

‘Slut! Whore!

The use of these words causes a justified feeling of indignation. But is this indignation removed in a sexual context? Are these words okay, empowering even, in a sexual setting where we feel safe? Do these words secretly thrill us when used consensually and within the confines of the bedroom?

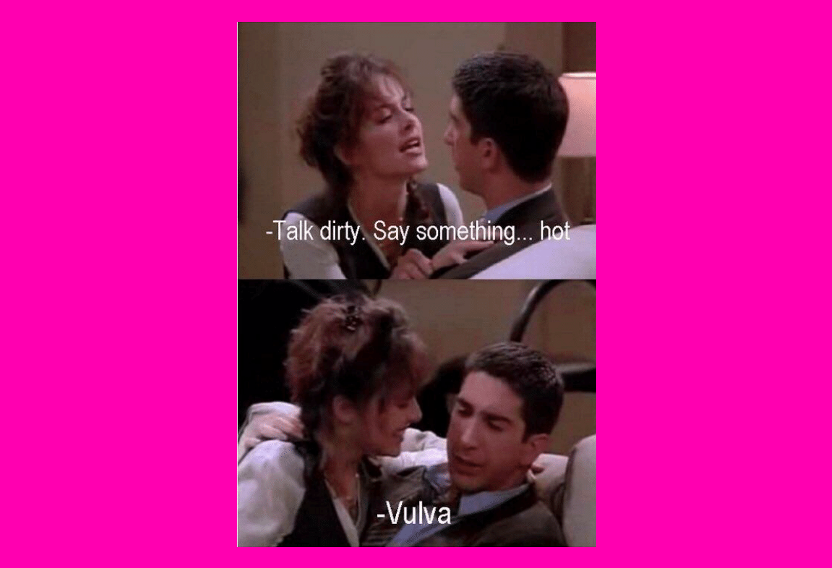

Much like Ross from Friends, my first dirty talk experience wasn’t up to scratch. I was tongue-tied, awkward and embarrassed. I couldn’t open my mouth and say anything. When I finally mustered the courage to utter something, it wasn’t as bad as Ross saying ’vulva’, but it wasn’t too far off. It took countless awkwardly honest conversations with previous partners and many scandalous, over-sharing wine nights with friends before I finally managed to communicate openly during sex. And it was glorious.

Until that night.

It was going wonderfully. A university night out, flirting, dancing and raging hormones on the loose: we went back to his at the end of the night. Clothes came off and we were having a great time. And then I heard those words from above: ‘Who’s my slut? Who’s my whore?’

These words had a strange effect on me. A part of me froze in horror, but there was another little part of me that... loved it. It wasn’t until the following morning, nursing a tremendous hangover, that it hit me what had happened. You see, for me, there was a difference between saying what felt good and being told that I’m ‘a fun little slut’. Even writing these words so publicly is nerve-wracking, but, as the theme is here: it’s important to talk about it.

Let’s examine some of these words.

Whore has a Germanic root in ‘horaz’ which means ‘a person who desires’. Note the emphasis on ‘person’ and not ‘woman’. Its emergence in the Bible through ‘The Whore of Babylon’ was perhaps its first tentative steps towards the derogatory meaning we associate with it today. In the 14th century, a slut, on the other hand, was used to describe an untidy or dirty woman. Chaucer describes an untidy man as ‘sluttish’ during this period. It wasn’t until 1966 that slut started being used to shame women for ‘excessive’ sex.

The point is that now these words are used to degrade and shame women for showing sexual desire. These words are part of a system that threatens not only a woman’s right to sexual self-expression but also her right to choose what to wear in the morning in the fear of being labelled a ‘slut’. A huge part of a woman’s shame surrounding sex comes from the language we use. Under no circumstance should the effect of these words be taken lightly. So, why do some of us enjoy, or even feel empowered by, the use of these words during sex?

Enjoying something sexually does not have to mean that we enjoy it socially. As Esther Perel says in her fabulous TED talk The Secret to Desire in Long-Term Relationships, ‘most of us are turned on at night by the very same things we demonstrate against during the day.’ It’s important to remember that our sexual desires do not define us entirely. Sex is just one part of our existence; we have jobs, friendships, relationships, interests and ambitions which all contribute to forming who we are. Sex is but a part of what makes us, us.

Photo by Jason Leung on Unsplash

Humans are complex. Our desires don’t always make sense to ourselves, and it’s important to approach desires open-mindedly.

We shouldn’t set limits on ourselves just because we think we understand how we work. It’s important to question why we like certain things; why we like to be spat on during sex but spitting on the street is perhaps unseemly. Or why we like a bit of hair-pulling when we’re turned on but we count the individual hairs we’ve lost when brushing our hair too rigorously to get the knots out. However, this why question, whatever the answer is, should not shame us. Shame was created as a way of controlling minority groups and, in this context, has led to ideals of what a woman ‘should’ be. We see this often enough through slut-shaming. However, honesty with ourselves and our desires can never be shameful when explored with care and caution.

I asked myself this ‘why’ when it came to talking openly during sex and then again in my encounter with Mr Who’s My Slut. Being aroused and also disgusted meant I had to sit down and have a very honest conversation with myself and my relation to shame. A few years later, I had a new encounter. It was equally as ‘eloquent’ but this time it was different - better. Why? Because of all-important communication. The ability to talk about what turns you on and being brave enough to have a voice in stating what you like, no matter what it is, is vitally important.

Mr Who’s My Slut can be strikingly compared to Mr Eloquent. The first time, there was no communication about if this way of speaking was something I enjoyed; he didn’t ask and I didn’t know. That was the problem, not the words themselves. Mr Eloquent told me that talking turned him on and he was hypersensitive to it. He asked me if it was ok for us to communicate in this way during sex and if I was comfortable.

So I tried it again. The small arousal part which I had previously squished and felt ashamed of suddenly came alive. I enjoyed it.

I was not afraid to make noise or to say when I wasn’t enjoying something. Calling myself filthy things empowered me. When there is consent and communication, sexual enjoyment is a wide spectrum of possibility.

Illustration by Anya-Lee Temple

However, there is an argument to be made that the joy of being called such vulgar things arises from an ingrained sense of shame, internalised misogyny, which is the direct product of female oppression.

But, there’s also a power in reclaiming such labels in a consensual, safe environment with a sexual partner. Being able to use such language in a way that turns us on can be a powerful tool in sexual expression.

Social scientist Mike Anderson states that couples who share their sexual fantasies, even if they don’t end up doing them, report significantly higher levels of sexual satisfaction. Of course, this is even higher if these fantasies are carried out. But once again, the same conclusion prevails: communication is key. Just by saying that you’re fascinated with the idea of role-playing a sexual version of The Great British Bake Off in your kitchen could significantly improve your sexual satisfaction. It’s mind-blowing what a little honesty can do.

Many people, especially women, struggle with speaking up during sex. This is no surprise when, for centuries, sex has been seen as a woman’s obligation rather than a source of pleasure. Nowadays, this discourse is in the process of being challenged (thank god) but there are still millions of women out there too afraid to speak up and say, ‘Actually, my clit is around two centimetres lower than where you are right now.’ Dirty talk aside, sometimes, even voicing female anatomy is an issue.

Sex educator Kenneth Play commented on dirty talk as ‘carving out an erotic space where dirty talk is about fantasy and not about how you feel about that person in reality’. This is very important. It’s ok to leave certain meanings at the doorstep of the bedroom. It is okay to enjoy these words during sex and be repelled by them in the outside world. Surely, the right to stand up against such verbal injustices should go hand in hand with the right to be empowered or even turned on by them?

It is also okay to not enjoy them at all. The important thing here is the right to our voices. The right to say yes, no and even the right to just talk about it, even if it seems taboo.

It’s important to talk about it.

Art by

Words by

Share this article