has covid-19 worsened the north-south divide?

By Florence / 26 October 2020

Over a hundred years ago, one of history’s worst pandemics was sweeping the globe. The Spanish Flu killed over 100 million people, 5% of the world population of the time.

Facing the tail end of WW1, the British government championed ‘business as normal’, hesitant to close factories that were vital to the war effort. In Manchester, however, the city’s health secretary, Dr James Niven, was heralding a different approach. Niven recommended shutting schools and cinemas, advocated for physical distancing, and distributed information pamphlets to residents on reducing the risks of infection. Niven’s advice was, however, ignored by public health officials in Westminster to the exacerbation of the UK’s death toll. Events of the past week have rhymed with those of 1918, when Whitehall and Westminster openly ignored calls from local authorities in the north of England as they battled a surge of Covid-19 cases.

Greater Manchester, Liverpool city region, South Yorkshire and Lancashire have now been placed under the most severe Covid restrictions as part of the government’s new three-tier plan. Under new measures, pubs and bars have been forced to close, and bans have been placed on inter-household mixing. The ‘levelling up’ of restrictions in the North is necessary and, if anything, majorly overdue. At the time of writing, Covid-19 cases have reached 273 per 100,000 in the North West and 241 per 100,000 in the North East. Comparatively the South East is experiencing 35 cases per 100,000. Despite this discrepancy, Independent SAGE advised the government in late September to impose a nation-wide circuit breaker, placing the entire of the UK back into a lockdown akin to that in March. However, rather than following scientific advice, Boris and his coterie instead have imposed experimental lockdowns across the North with little care for the consequences on local communities.

When Covid-19 took hold in the UK in March, London was the epicentre.

The densely populated public transport systems and a high rate of international visitors made the capital bear the onslaught of the virus before the rest of the country, and lockdown was a reaction to this. When restrictions eased nationwide in July, many Northern cities were yet to experience their spike and their infections were, in fact, increased further as a result of economic stimulus schemes such Eat Out To Help Out. The sudden restrictions imposed on the eve of Eid al-Adha in Greater Manchester, which banned interhousehold mixing in houses or private gardens and sparked accusations that Downing Street was unjustly targeting Muslim communities, evidence the flaws of a centrally-devised coronavirus response that is ignorant to the economic and social nuances of the UK’s differing regions.

The consequences of premature and unsteady easing of lockdown measures in the North East and North West were exacerbated by the deluge of students returning to northern metropolises in September. Cheek-by-jowl student housing, often situated in low-income areas, meant the virus spread rapidly through cities such as Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds; cities that are flanked on their peripheries by industrial warehouses and factories that offer hourly-paid, unsafe, work and have, as a result, witnessed a significant number of outbreaks. Had the government’s £10bn track-and-trace system been at all effective the severity of spikes in the North could have been avoided. PHE, however, did not predict the limited capacity of a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and subsequently failed to report 15,841 new cases between 25th September and 2nd October.

When the government announced the increased tier-3 restrictions for Greater Manchester, Mayor Andy Burnham requested a package of £90m that would cover an 80% furlough and self-employment scheme, protecting his citizens from further economic damage. At the time of writing, Westminster have agreed to grant the city £22m for track and trace, yet are offering no more than £60m to assist with the effect measures will have on businesses. Liverpool, Lancashire and South Yorkshire are receiving £30m each for business support schemes, approximately £20 per person. MPs in Greater Manchester are yet to reach a final agreement with Westminster, due to the latter’s inability to account for the further impact restrictions will have on Manchester’s transport links and airport. Burnham has also highlighted that many Mancunian businesses have been under restrictions since July, meaning they will feel the impact of the latest tightenings even more acutely. In a moving speech to the press last Tuesday, Burnham recalled the historical hostility between the Tories and Northern workers, stating that “Greater Manchester, Liverpool and Lancashire are being set up like canaries in a coal mine for an experimental regional lockdown strategy”.

Burnham’s sentiment is especially affecting when we consider that Boris Johnson, whose attitude towards northern constituents can be surmised from his 2004 editorial in The Spectator that stated how Liverpudlians possessed a “peculiar, and deeply unattractive, psyche” and touted “an excessive predilection for welfarism”, arguably owes his current position to voters across the north of England.

Photo by Viktor Forgacs on Unsplash

In the last election, Labour supporters watched in horror as the so-called ‘red wall’ of northern seats crumbled to the Tories.

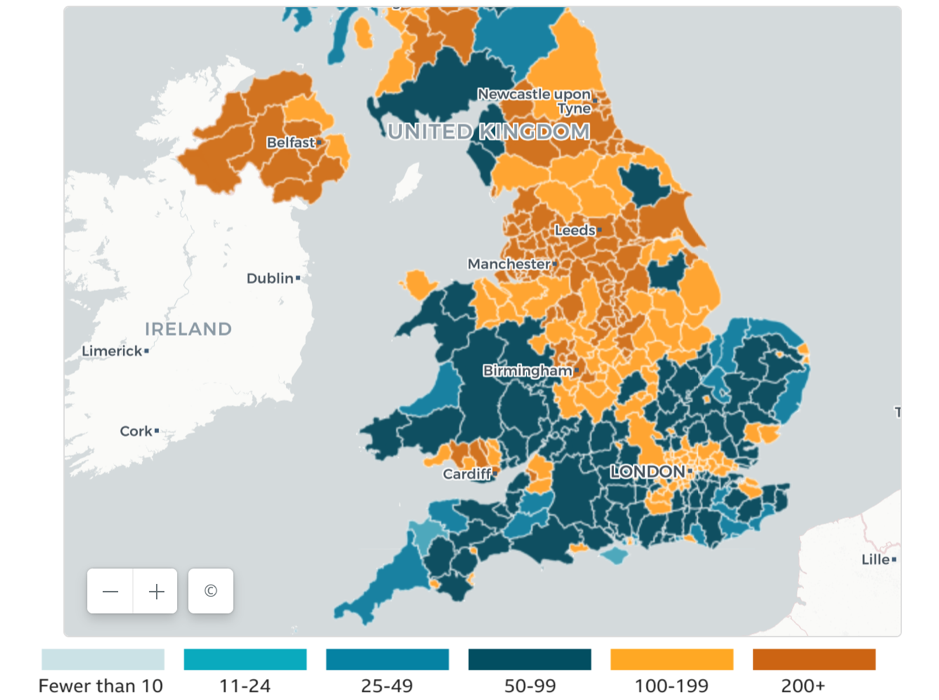

Leave-voting former mining communities such as Wokingham and Bishop Auckland- Labour seats for 100 and 85 years respectively- embraced a Conservative party that promised to deliver on Brexit, despite laying these towns to waste in the 1980’s. One year later and a heat map of England shows the real ‘red wall’ to be a continuous high band of Covid-19 cases running from Liverpool to Newcastle.

The North is not homogenous, nor is it barren, or grim, or backwards; it is a diverse and fruitful region filled with people doing their best to thrive despite adverse circumstances.

A 2018 report by IPPR North found as many as 2 million adults and 1 million children are living in poverty in northern areas, and spending per head in London to have increased by twice as much as spending in the North since the launch of George Osbourne’s 2014 ‘Northern Powerhouse’ initiative. Furthermore, northern regions have England’s lowest life expectancies-- in Blackpool the average male lives to 68, compared to England’s average of 79. These social, economic and health inequalities have only worsened over the past 7 months.

It is easy, and worthwhile, to recognise a North vs. South divide in the political events of the past week and paramount that Westminster and Whitehall are held to account for their failure to protect northern citizens. Yet these grim statistics and the worrying indications they hold for winter also evidence the urban-and-lower-income vs. others divide, and demonstrate how sustained inequality in one place cannot be remedied by sudden decisions executed in a geographic and social elsewhere. While our government is intent on siloing regions off as human shields, other countries have demonstrated how cooperation of local and national authorities have helped to control the virus. In what is arguably the most fractured milieu of British history the fight for social cohesion has never been so vital, so, despite the nationalistic rhetoric it may incur, in the battle against coronavirus Britain is undoubtedly stronger together.

Words by

Share this article