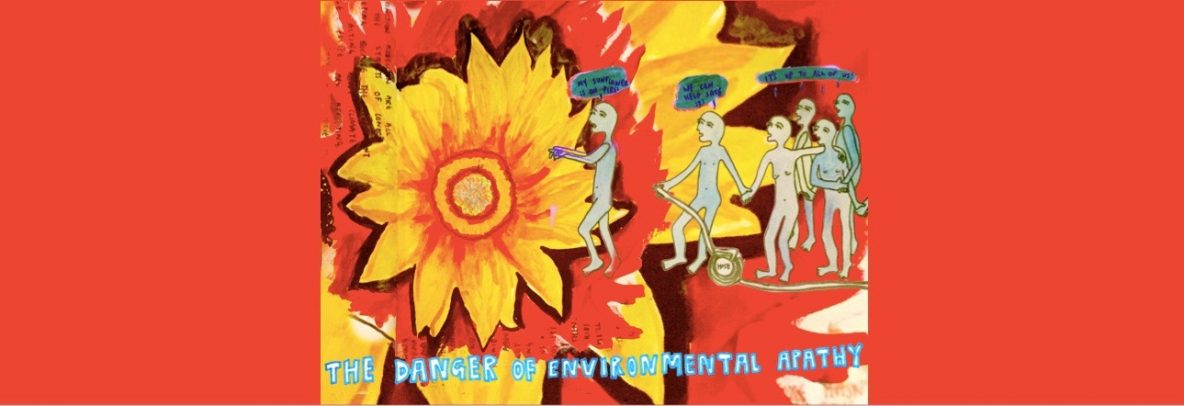

The dangers of environmental apathy

Why we need to stop blaming everyone and everything else and take action!

By Anna Stacey

Illustration by Megan Lewis

‘Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for reducing pollution, but I’m just too busy to walk or cycle.’

‘I would stop eating beef, but burgers just taste too good!’

‘I would do more for the environment, but realistically what difference will one person make?’

How many times have we heard – or perhaps made – these excuses for not doing more to combat climate change? And yet scientists are continually warning us that we now only have 12 years left to stop global temperatures rising more than 1.5 degrees. Why, despite knowing the facts and the urgency of the situation, do we still not do everything in our power to prevent climate change?

Many researchers have put this down to environmental apathy. According to an EPCC survey, compared with other European countries, the UK is the least concerned about climate change, with ‘only 20% indicating they are extremely worried’. Some claim the enormity of the situation is so overwhelming that they feel a sense of powerlessness. Scientific studies reinforce this idea, claiming that, for many, not being more environmentally active stems from unconscious denial caused by extreme anxiety, functioning as a defence mechanism against the truth. Could it be that we aren’t apathetic, but simply in denial?

Well, the EPCC report suggests we are experiencing something in between apathy and denial. It claims that climate change is seen as a ‘distant threat’, temporally, geographically and socially, which is why we continue not to act.

To break this claim down: ‘temporal distance’ refers to the idea that climate change will only have implications so far in the future that they will not affect us. Research from Harvard psychology professors suggests that the human brain is simply not equipped to respond to threats so far ahead, but only to more immediate, short-term dangers. Unfortunately, short-termism is also engrained in almost all economic and social institutions within capitalist society, making it even harder to achieve effective change.

‘Geographical distance’ suggests the belief that the effects of climate change will be felt far away from us.

And to some extent, for those in Western cultures, this is true. In all likelihood, it will be those in developing countries who will be the first victims of climate change, not the wealthy Westerners who take environmental risks regardless (a true sign of privilege).

Similarly, ‘social distance’ refers to the idea that the consequences of 'climate change will never affect someone like me'. This common delusion has been coined ‘optimism bias’ by scientists. Just as we assume we won’t be the ones to get divorced or hit by a car, we also assume that we won’t be so unlucky as to be the victim of a natural disaster triggered by global warning.

An alternative potential explanation for our collective apathy is the so-called ‘sucker effect’ (also known as ‘free-rider effect’): the theory that the bigger the group of people, the less effort individuals contribute to a common cause because they see themselves as dispensable. So perhaps this apathy comes from the belief that our personal actions won’t make any difference, or even a fear that we won’t be able to see any results.

However, the idea that one person can’t make a difference is a troubling misconception. Whilst it might be true that one person choosing to recycle or become vegan will not solve climate change, it is at best a fragile excuse for not doing your bit and at worst a dangerously misleading idea. Environmental apathy can be compared to voter apathy (‘my vote won’t count, so there’s no point in voting’), in that it underestimates the power of the collective.

One person’s actions alone have relatively little impact, but if we all reduce our meat and dairy intake, or all decide to ditch single-use plastic, then this will have a significant effect on the environment. It is important to remember that collective movements such as these rely on continued individual choices and actions.

Another common argument is that it is not within the individual’s power to tackle climate change because it is really only governmental policy and big corporations’ decisions about fossil fuel usage that can prevent global warming. It is true that political decisions are fundamental to solving climate issues and that our current neoliberal consumerist society is one of the main barriers preventing this. However, this is not a reason to stop making sustainable individual choices. The recent rise of veganism is a prime example of how market-led movements can force suppliers to radically change their products, reducing their impact on the environment.

Defeatist reasoning demands change only from others and relinquishes our personal responsibility to society and the planet.

Believing policy change is our only hope is not a reason to sit back and blame the government; if anything, it should galvanise us to get out there and start campaigning. It is crucial not to forget the power of protest in motivating the government to make environmental policy changes.

So how can we possibly break this paralysing inertia? Writer and activist Rebecca Solnit has two important messages that might help. Firstly, ‘the future hasn’t already been decided’. Whilst it is undeniable that climate change is happening and will affect us all, it is still within our power to prevent the worst-case scenario. Secondly, she states, ‘personal virtue only matters if it scales up’. Yes, our individual actions make a difference, but this requires us all to do them. So, stop taking Ubers when you feel lazy, give up meat and dairy sooner rather than later, join Extinction Rebellion, but, most importantly, tell your dad, educate your mates, get your gran involved, because without them we can’t defeat this collective apathy.

Art by

Words by

Share this article