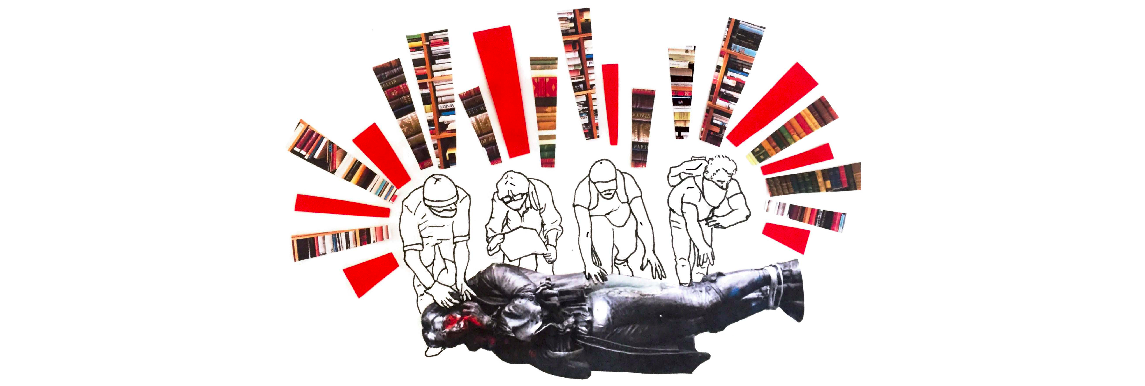

We Can't Pretend that statues were meant to teach us anything

Why it's important to keep up with history and tear down the statues that no longer serve us

By Anusha Persson / 3 July 2020

Illustration by Elsa Pearson

Any argument that statues are a useful teaching tool in history fails to consider their current reality. In our daily spaces, they have become part of the faded architecture, representing someone who was once illustrious to history but failing to provide context because, well, they're statues.

But let's get this straight, a statue was never intended to teach us history.

The classicist and Oxford University lecturer Peter Stewart writes in his book how 'The statue was social art with a perceived social function'. Statues were erected to glorify an individual, to commemorate their efforts and to celebrate their power status. Whether it was to celebrate Britain's colonial efforts or to commemorate the World Wars, people in power erected statues to celebrate victories. They were intended to celebrate a sense of power and achievement, to establish a 'great man narrative' of history and to show a hierarchy.

We can't believe that erecting a statue is a valuable teaching moment, or that a statue is a moment of unbiased reflection of a historical event. In fact, statues obscure our visions of history every day. Visitors to Barcelona could be forgiven for believing that Colombus had a great impact on the city due to his presence on the end of La Rambla, when his links with the city are tenuous at best, and this focus on Colombus steals attention from a proper consideration of Barcelona's links to Cuban and other colonies' slave trade.

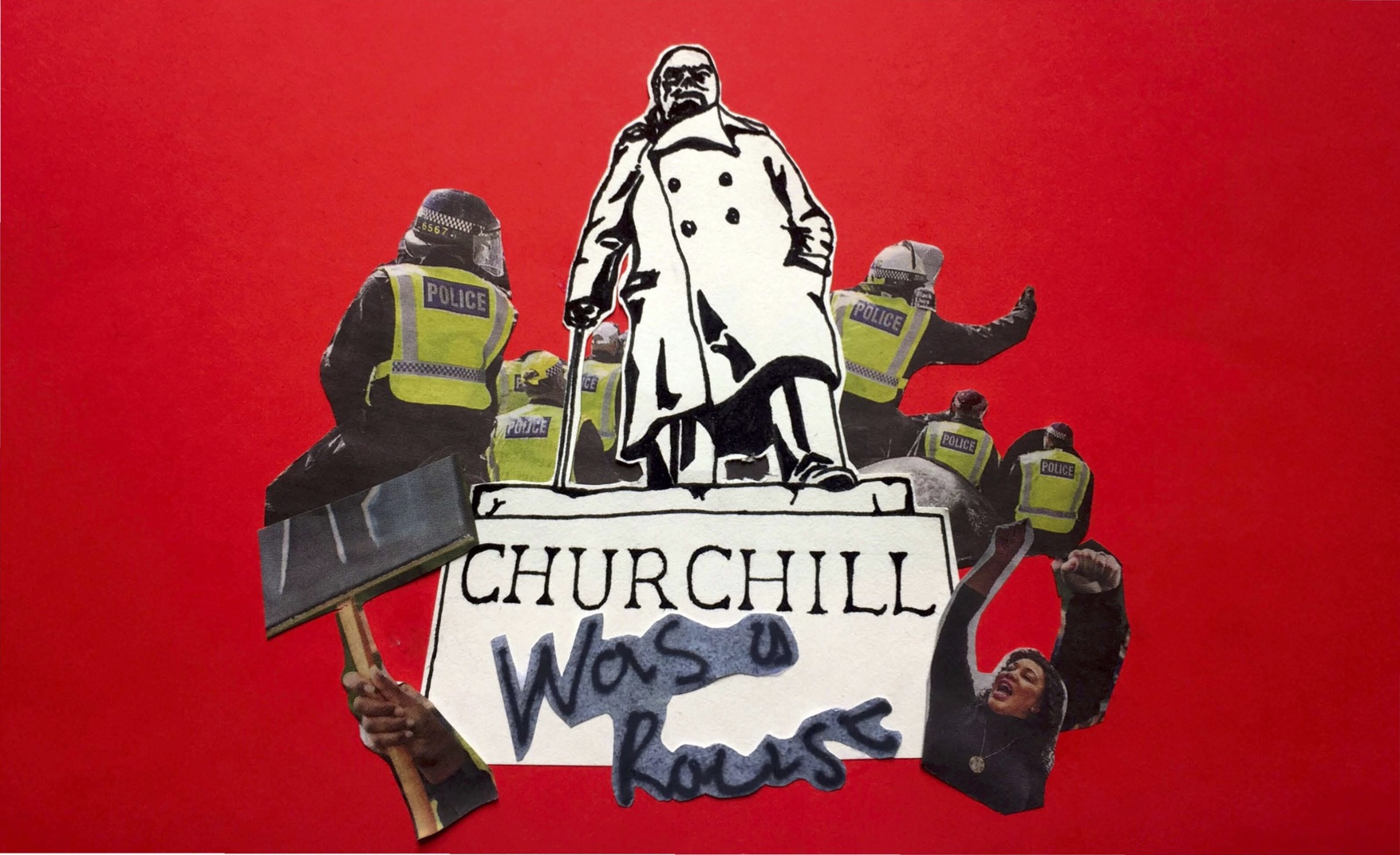

Yet, this is what our history teaches us, isn't it? All of us who sat through British history lessons remember hot summer afternoons listening to teachers describing Henry VIII's split with the Church. Those of us whose family came from ex-colonies will remember squirming in our seats when teachers describe Churchill's greatness, a version of history which is frustratingly over taught and at odds of what we have heard about injustices in places like Kenya, India, South Africa - injustices suffered by our own family.

We have never decolonised our view of history. In our interpretations, the empire just went - taking with it all the injustices and violence that it wrought and the calamities that it caused.

And, this is why we still have the statues up. Our governments are too comfortable to remain hinged on blinkered interpretations of history which prop up their decisions. If the nation had been taught sufficiently about the patterns of West Indian migration to the UK and their important role in rebuilding Britain, then how could the Conservative government have justified the Windrush scandal? If we had learnt fully about the UK's history of systemic inequalities, then would there still be a deafening silence surrounding Grenfell?

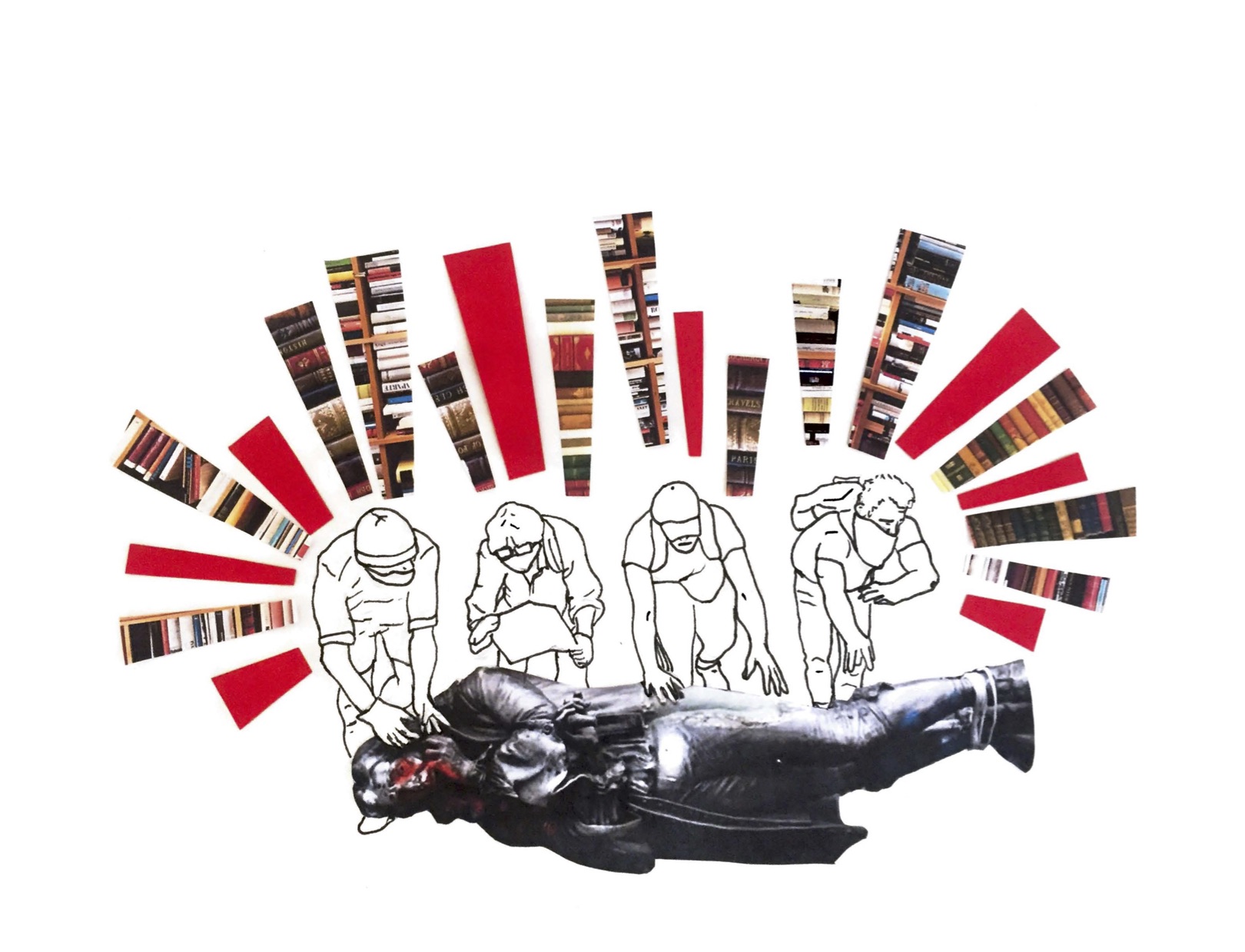

Statues erected by previous governments have only ever been intended to commemorate a vision of history which glorifies past holders of power in society. They rob our ability to sufficiently evaluate these individual's actions and commemorate the victims of their atrocities.

We are gaslit into believing that these statues were intended to teach us a vision of history, that they are some kind of objective knowledge-sharing exercise, to reveal our nation's past. We are gaslit to believe that their presence is a harmless reminder that our nation once did something sort of bad, but, thankfully, we have this statue to remind us how far we've come and how much we've changed.

No one is going to forget Churchill if we take his statue down. Taking down our statues doesn't mean we're going to forget our history, it only means we'll be able to remove our blinkers from how we understand our past and allow ourselves to critique it more profoundly. Removing our statues opens up conversations about our history, and now more than ever the British public have been forced to reconcile with the atrocities committed by some of our supposed victors - Gladstone, Churchill, Disraeli.

If we choose to let the statues remain standing, we risk the danger of losing these conversations, of not finishing through on our pledges to 'decolonise' our society. Taking down the statues is by no means the end of the conversation, but rather, it is an opportunity to readjust how we view our history and open up a greater conversation about our racist past, and how this has contributed to our racist present.

Art by

Words by

Share this article