Why student 'disobedience' deserves your attention this lockdown

By Lily Owen / 12 November 2020

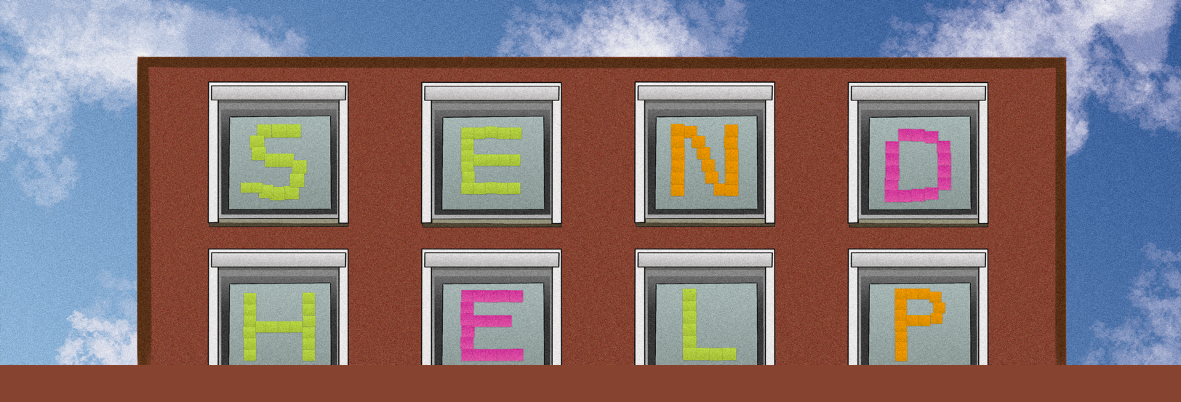

Illustration by Eloise Stringer

It has been a comfort for students and young people themselves that they are at far less risk from COVID-19 than their elders. Nonetheless, it is becoming ever clearer that this pandemic is fuelling the fire of another, one that arguably puts younger people at a greater risk: the crisis of mental health.

Never in our history have we quarantined healthy people. By shutting everyone indoors and restricting their social interaction to prevent the spread of one disease, we are subjecting people to another. With students making up such a large proportion of these asymptomatic, or at least low-risk, individuals, there is a build-up of frustration and longing to interact within a social group that is largely considered to be safe – so what is wrong with that? Primarily, it is considered selfish. This is a global pandemic and one that does not discriminate between generations; young individuals have died and some with no underlying health issues. In a black and white reality, it is selfish to flout the rules. However, the current situation is one that no one has been taught how to handle, making every feeling, no matter how selfish or ‘wrong’, valid. There is no excuse for disobedience, but there is context and consideration to be applied.

Boris Johnson warned young people against “complacency”, Matt Hancock begged them, “Don’t kill your gran”: it has become a widely accepted belief in political, scientific, and social circles that the younger members of our population are the cause of a rise in cases. Yet, there is a significant level of irony here when acknowledging the number of school-leavers and students that are operating the Track and Trace call and testing centres and being paid minimum wage to do so. The generation who is being sought out as a scapegoat for the rise in COVID cases is the same generation holding together a multi-billion-pound system that the government has totally mismanaged and throws the entire calculation of cases into question.

Some may say students are to blame for the spike, others might say that a mass stag hunt of at least 30 riders and over 100 followers with a large number of elderly, vulnerable people funded by a £10,000 grant and £50,000 loan from a taxpayer-backed coronavirus scheme could also have played a part. Whilst we are busy deciding whether or not to report neighbours we suspect have broken social distancing regulations, let’s also remember the part played by the government and its friends.

Photo by Sasha Freemind on Unsplash

The protection of our wider society’s physical health is one thing, but where is the protection of our mental wellbeing?

Hillary Gyebi-Ababio, from the NUS, expressed hope that educational institutions could adopt a ‘care-centred approach rather than fall back on academic sanctions that will only create further harm.’ Calls for expulsion as punishment for parties and mixing could be ‘hugely damaging for their futures at a time of rising unemployment, a growing student mental health crisis and uncertainty over future opportunities.’

Working as a student ambassador for the University of Leeds, I have witnessed first-hand students coming to me breaking down in tears over their only friend in their flat dropping out, leaving them with no one; students feeling intimidated and panicking about how to join societies on their own with all socials being held over Zoom; students venting their anger at the lack of communication from their faculty about the new online lecture system. In one case, this meant that one individual missed access to weeks’ worth of content. In another extreme case, the university deemed it appropriate to only inform an international student that his MA was starting in January rather than September, a day before he was due to fly to the UK, leaving him potentially paying for accommodation with no student loan for what he thought was to be his first semester.

You hear an awful lot about the hundreds of students who have gathered for parties in their accommodation and ran from the police when they were shut down, but you don’t hear the other side of the coin. What is not highlighted in these news stories is the added pressure and rising levels of anxiety amongst these groups, or how many students have died from drug related incidents as part of these gatherings. Whilst being shut indoors is one method to keep people safe, it is also another to inflict harm. An absence of nightclubs and the closing of pubs at 10pm is thought to deter alcohol consumption and drug use, but in reality, it is arguably turning people to them. A night out with your friends is considered a good time, possibly enhanced by alcohol and drugs, but, for many, in the absence of this environment and the company, alcohol and drugs are all that are left: the sole remainder of that ‘good time’. As people resort to taking these activities home, usage becomes excessive and, in a rising number of cases, fatal.

Photo by Dan Meyers on Unsplash

Rightly so, the initiative of support bubbles has been granted to those living alone. Yet, what if you lived in a flat of five, where one person dropped out, two decided to move home to save money, and one never came out of their room: is that not just as damaging as being physically alone? That is a very real scenario for a lot of students right now, but where is the support? Speculations about whether or not people will make it back home for Christmas is inducing further anxiety, as well as taking up conversation from areas of more imminent importance: how can support be accessed, what management techniques can be adopted, who is there to talk to?

Young people’s worries are not only about keeping physically/mentally healthy at this time, but about maintaining financial support in an exhausted job market; making new friends in a new city, where socialising is severely capped; adapting to learning independently for a degree that is costing them years of student debt and for a job that might now take another year to achieve. These challenges were already new and daunting to those leaving home for the first time, but now they are steeped in further uncertainty.

As people, such as Piers Morgan, so love to compare this pandemic to the sacrifices of previous world wars and how everyone rallied together, what is neglected is our much wider knowledge of mental health today. It is a common trope to look back on previous victories as a great mark of our strength, ignoring the weakness; however, just as WWII gave birth to the Paris Peace Treaties, it also unleashed a wave of PTSD and depressive symptoms upon a global generation of war veterans. What is different and should be different about our approach to coronavirus is our awareness of, and preparation for, such negative impacts.

As we head into a second, winter lockdown, Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) already threatens to rocket the level of people of all ages suffering from depression and anxiety.

1 in 4 people experience a mental health problem every year and it is evident that lockdown’s removal of many coping strategies – spending time with friends and family – will have a catastrophic effect in the build-up to Christmas. Where the government is removing freedoms in the pursuit of health, it needs to also provide remedies for the negative effects of this action. Student disobedience in lockdown deserves more attention right now and not just in the form of slandering news articles. The generation gap is playing a great part in this ‘blame game’, evidenced in the remarks made by Johnson and Hancock, pitting people against one another to source blame outside of Westminster. It is the young killing their grans and the old out of ignorance, and it is the old suffocating the young by limiting their freedoms in line with their own. However unfortunate, poor mental health is what can currently bridge this gap between opposing groups in lockdown, with over two-fifths of people aged 70 and over in Great Britain having also had their mental health affected by coronavirus.

I am not trying to compare a student kept in university accommodation with catered meals and a student loan to an elderly person on their deathbed, or an individual who has been shielding since March. Instead, I mean to encourage consideration of the impacts experienced by all members of society, and an effort to try to understand everyone’s unique situation. The first example may seem less desperate and life-threatening, but that is what hospital admissions and COVID death counts have mistakenly overshadowed thus far. The argument that people’s lives are at stake is absolutely the case – it’s just that not all of these lives are being taken by the virus itself.

Rather than generalising the young population as one ignorant, selfish community, we have to contextualise these incidents in the light of their own unique struggles. An entire nation’s future is invested in this generation’s education: government policy cannot afford not to empathise with and support its students.

Art by

Words by

Share this article